![]() Teaching A Computer To Draw_

2025

Teaching A Computer To Draw_

2025

Code, Screen, Mac Mini, Plexiglass

*This work is not a video work, everything is happening in real time.*

55 x 45 x 5 CM

Shown as part of a group exhibition at Konstakademien (Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, Fredsgatan 12) in Stockholm, Sweden 🇸🇪. The show had to close early due to a fire at the premises on June 7, 2025.

Exhibiting artists:

Esmeralda Ahlqvist, Jaana-Kristiina Alakoski, Silja Beck, Viktor

Berglind Ekman, Isolde Berkqvist, Johanna Bjurström, Elmer Blåvarg, Moa

Cedercrona, Niels Engström, Aron Fogelström, Anton Halla, Lewis

Henderson, Sanna Håkans, Alden Jansson, Marie Karlberg, Andrea

Larsson-Lithander, Jost Maltha, Caio Marques de Oliveira, Kayo Mpoyi,

Therese Norgren, Sofia Romberg, Maria Toll, Cilia Wagén, Joi Wengström.

With thanks to Daniel Norrman, Jenny Olsson, Johanna Gustafsson Fürst, Silvia Thomackenstein and Jean-Baptiste Berangér.

You can find the 2025 year’s catalogue here (under Publications). It has been published and made available based on a printed publication.

![]()

This work emerged from a curiosity with the potentiality of algorithms, not merely as technical instruments, but as autonomous actors within the aesthetic field—a coded entity capable of generating, in real time, gestures and deviations. I wanted the creative endeavour to be delegated to the machine. For it to produce something from a set of rules, set out by the artist in advance. Something both absurd and sublimely mundane, shuffling round desktop icons in an attempt to replicated patterns taught from inexact source material. The

artist is recast, not as maker, but as a facilitator

of code and implanted ‘props’ rather

than outcomes—abdicating authorship in favour of procedural emergence.

What new aesthetic forms might arise, when the artist recedes, and the algorithm is left to fill the void?

I didn’t want to make a fictitious screen capture video where the computer

seems to draw. I wanted the computer to produce something in real time. Sometimes it ‘fails’, in comic and absurd ways, unable to function on time

without error, pushing it to spiral out of control and create things in moments

where it seems to have a life of its own, desperately trying to catch up with

itself. This is where it becomes really interesting, the moments where it

begins to act irrationally, at times it seems almost slapstick (or human-like).

It is precisely this quality of non-linear

authorship, of

relinquishing control to the machinic logic of the system, that I sought to

explore.

This echo’s Nicolas Bourriaud Relational Aesthetics but updated for

a moment in which not only the social-bond, but the internal logic of our

devices has been fully commodified.

Machines that we have poured ourselves into

over the past two and a half decades. Machines that we use to isolate ourselves from other

living things, and use as an extension of our Being. These digital

infrastructures, while coded to perform functional, extractive tasks, contain

within them the latent potential for misuse.

Exhibiting artists: Esmeralda Ahlqvist, Jaana-Kristiina Alakoski, Silja Beck, Viktor Berglind Ekman, Isolde Berkqvist, Johanna Bjurström, Elmer Blåvarg, Moa Cedercrona, Niels Engström, Aron Fogelström, Anton Halla, Lewis Henderson, Sanna Håkans, Alden Jansson, Marie Karlberg, Andrea Larsson-Lithander, Jost Maltha, Caio Marques de Oliveira, Kayo Mpoyi, Therese Norgren, Sofia Romberg, Maria Toll, Cilia Wagén, Joi Wengström.

With thanks to Daniel Norrman, Jenny Olsson, Johanna Gustafsson Fürst, Silvia Thomackenstein and Jean-Baptiste Berangér.

You can find the 2025 year’s catalogue here (under Publications). It has been published and made available based on a printed publication.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Teaching A Computer To Draw_2025 - install

Teaching A Computer To Draw_2025 - screen recording

Teaching A Computer To Draw_2025 - screen recording *quick*

Teaching A Computer To Draw_2025 - install *quick*

![]()

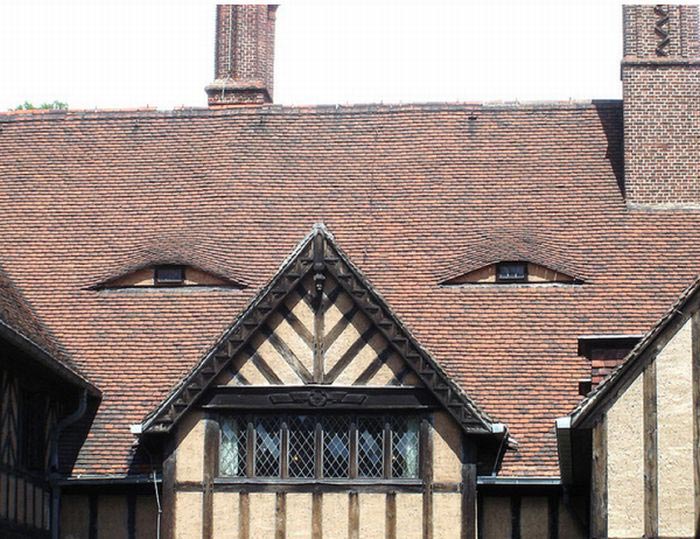

The

computer sits in its Plexiglass box, separated from the room, not

connected to the internet — quietly scanning images looking for smiley faces,

hearts, eyes. The kind of symbols you see every day and forget about. Like a

car number plate that seems to spell out initials of a loved one. Or a cloud that

looks a bit like a dog. You might think it’s coincidence. The machine just reads it as

data.

It’s

trained from an ambiguous data set—imagery that can be interpreted, or misinterpreted,

in multiple ways. Symbols that coincidentally appear in

our everyday lives. Like a rock that resembles a love heart. Or, birds in the

sky that look like a cartoon face. But the machine just looks for patterns in pixels. It doesn’t see the birds, the sunset, or the face it resembles, it only sees the combination of pixels that we interprit as images.

What does it understand of the world if it only looks for patterns and symbols?

It doesn’t care if the smiley

face means happiness, or if it is ironic. It just logs the curve of the mouth and

tries to replicate it. It just draws because that’s what I told it to do, it doesn't think, we just want to think it can, because we are alone and that’s completely terrifying.

“those who succumb to the seductions of robot companionships will be stranded in relationships that are

only about one person… the absence of the emotion [on the part of the computer] reduces

the scope of rationality [for the human] because we literally think with

our feelings.” Sherry Turkle, MIT

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The

way one brain is wired, at a particular moment in time, is painfully alien to

all other human brains, and its past and future. Our way of thinking is unique,

constructed through lived experience. Unlike computers. For us it’s near

impossible to transplant ideas from one person to another cleanly. Our best

attempts are slow, murky and clumsy, completely abstracted and above all,

entirely tainted by the receiver.

Here’s Geoffrey Hinton talking about this:

We

do this by using verbal and visual language as our way of sharing our relative perception

of the world. Then we figured out how to distil information in

the form of symbols, writing, records, audio and data. The science fiction

author William Gibson thinks this tradition becomes like a prosthetic memory, completely

changing what it means to be human.

It captures something of the present moment, compresses it into something and sends it into the future so that it is another self, a

different self, can try to interpret the information.

Humans don’t just process

information. We project. We fantasise. We misunderstand — in ways that

are rich and complex and culturally shaped, and completely stupid. That is what

culture is, it’s what we have been building since our ancestors developed

language, a Mass Consensual Hallucination.

This, in a way, is probably the most important and futile thing we do as humans, because in a way it might mean we might just transcend time (and our own inevitable death).

Computers, however are fantastic at sharing information, much better than humans, and could in theory actually transcend human-time. They have the same thinking architecture and can be trained using massive

parallelism. This means they can be split across thousands of GPUs or TPUs,

processing enormous datasets. Once trained, the models can be

copied and deployed anywhere. Once known, once, known by all, forever.

Here’s William Gibson talking about this: