>Dub-Step_2024

Contact mic, Dub effects, Mac Mini, sound system, mdf, wood

>IG

Shown as part

of No One Is Bored,

Everything Is Boring, Galleri Mejan, Stockholm, Sweden 🇸🇪.

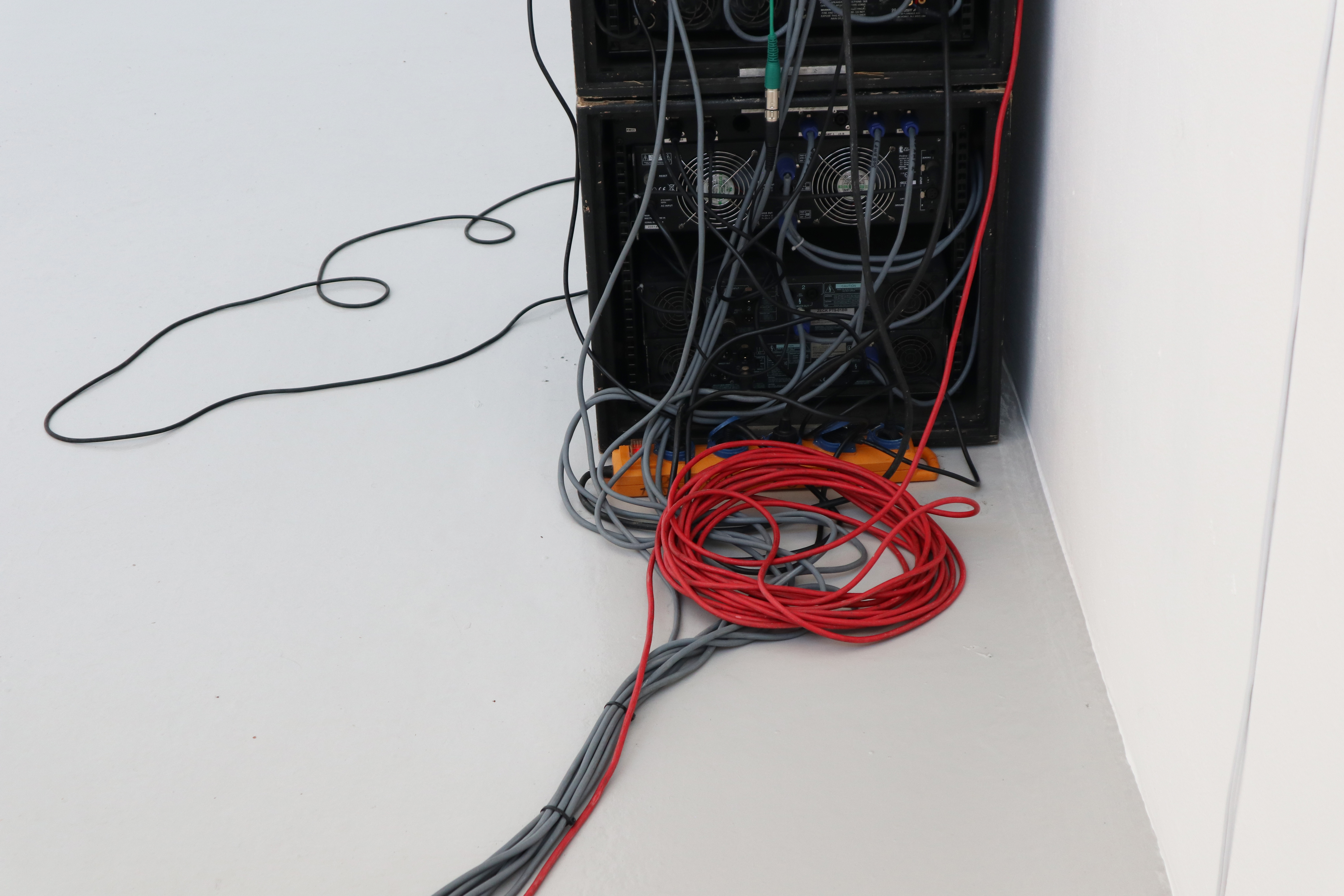

‘Dub-Step’

amplifies the sound of a viewer's footsteps when they walk on the yellow step placed in the doorway of the exhibition space. A contact microphone

picks up the sound of the footstep, running it through a series of dub effects before being

amplified through a powerful dub sound system.

![]() More text after documentation.

More text after documentation.

Back<

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Video documentation:

When I had the idea for ‘Dub-Step’ I wanted the ‘step’ to be really exaggerated. So much so it would become disorientating and absurd. The shock of the sound makes you instantly aware

of your presence in space, forcing you to interact with the work. It

brings to mind Darren Almond's ‘A Real Time Piece’ (1995).

In the sterile

whiteness of a gallery, it quickly becomes uncomfortable, almost embarrassing

to be the source of such a loud, resonating noise and its subsequent echo.

I think I was also thinking alot about Jean-Paul Sartre’s ‘The Look’—Being and Nothingness, p.317:

Let us imagine that moved by jealousy, curiosity, or vice I have just

glued my ear to the door and looked through a keyhole. I am alone and

on the level of a non-thetic self-consciousness. This means first of all

that there is no self to inhabit my consciousness, nothing therefore to

which I can refer my acts in order to qualify them. They are in no way

known; I am my acts and hence they carry in themselves their whole

justification. I am a pure consciousness of things, and things, caught

up in the circuit of my selfness, offer to me their potentialities as

the proof of my non-thetic consciousness (of) my own possibilities. This

means that behind that door a spectacle is presented as "to be seen," a

conversation as "to be heard."

...

But all of a sudden I hear footsteps in the hall. Someone is looking

at me. What does this mean? It means that I am suddenly affected in my

being and that essential modifications appear in my structure -

modifications which I can apprehend and fix conceptually by means of the

reflective cogito.

First of all, I now exist as myself for my unreflective

consciousness. It is this irruption of the self which has been most

often described: I see myself because somebody sees me - as it is

usually expressed.

...

Only the reflective consciousness has the self directly for an

object. The unreflective consciousness does not apprehend the person

directly or as its object; the person is presented to consciousness in

so far as the person is an object for the Other. This means that all of a

sudden I am conscious of myself as escaping myself, not in that I am

the foundation of my own nothingness but in that I have my foundation

outside myself. I am for myself only as I am a pure reference to the

Other.

What occurs when a

consciousness if forced to recognize that it exists not only as the centre of

its own being gazing outward, but also as a mere object in the world of others.

What ‘Dub-Step’ does, is it forces the person entering

the gallery to instantly become aware of the fact that they are in that room,

as well the fact that they have become an object or spectacle, within the gallery, in someone else’s

view. I guess this is what Sartre’s was trying to bring up, that

we are do not just merely exist alone, but as objects in the minds of a collective mass of others. We are shaped by the existential understanding that we are perceived, and that perception belongs to someone looking with an imbedded

societal framework that dictates their thinking.

I think I was also interested in the space where the show was, it’s a white

walled gallery. How does the audience experience work in a space that’s actually

quite alien from their everyday lives? Michael Dean, the British sculptor,

said something that stuck with me; “you go and have a look at art and there’s a

sense, that sometimes, that you’re braking it with your own interpretation

because you’re coming at it from a different history, or a different culture.”

I recognise that as a problem today. I don’t want that. I want to shatter that illusion

the moment someone steps into the space and force them to exist in the room,

rather than just in their own heads. It did scare a few people off, but other

began to play with the work, like you would play an instrument, their faces cracking like a

joke.

Now lets look at the Dub echo. A haunting from the past that persists after

the original footstep, returning to haunt the present... coming back again. And again. And again.

![]()

Photo of Lee “Scratch” Perry that I took back in 2013 when I interviewed him for NU Magazine

Dub emerged in Jamaica in the late 1960s as a radical reimagining of

reggae. Producers like King Tubby and Lee “Scratch” Perry (who I acctually met once) began stripping away

vocals, leaving the rhythm and bass to echo and pulse in new ways. With heavy

use of reverb, delay, and echo, dub created expansive, haunting soundscapes. This

experimental approach gave birth to a sonic world of endless possibility—an

atmosphere where the past and present seemed to blur, and time itself stretched

and warped.

Dub quickly became more than a genre; it became a means of

expression, both personal and collective, influencing not only reggae, but punk,

electronic music, and the cultural pulse of the UK’s underground sound-system

scene.

Sound-system culture,—mobile, community-based gatherings where DJs played

reggae and dub music—like punk, was inherently DIY. But unlike punk, dub and reggae, having an enherently black fanbase, had deal with sevier hostilities and barriers due to race relations in the UK in the post-war period. Opportunist

racist politicians like Oswald Mosley capitalised on the arrival of the Windrush

generation to stir hate and fracture race relations. This led to black music

including soul, reggae, ska, and calypso being omitted from the mainstream radio,

music charts, clubs or dances.

This meant fans of dub had to embrace DIY if they waned a music that represented both the diaspora and a music away from the mainstream. This DIY attitude manifested physically for this culture with each

piece of the ‘rig’ having to be portable and modular enough so it could be dismantled and fit in the back of a van. This shaped the sound of British sound-system culture, dub took on characteristics

from its Jamaican roots, but through differing social and geographical factors,

formed into something distinct belonging to the diaspora.

Dub, and the sound-system

scene, served as both a form of creative

expression and a tool for cultural preservation, providing a link to their

roots while also allowing them to redefine their identity within British

society. Dub and Sound-system

culture went on to inspire wide range of musical genres and cultural movements

in the UK including grime, jungle, trip-hop and Dub-Step—the latter comically giving

this work its title.

I think it’s funny how Dub, has permiated time, echoing and resurfacing, deforming into modern cluture, there is this great Marx quote “The tradition[s] of

the dead generations weigh like a nightmare on the brain of the living” from The

Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. There’s something haunting in this concept, like with Dub, where the past, be that its traditions or its culture, will always rise up.

Bringing this back to ‘Dub-Step’, the work that is, I think what I wanted people to get from the work, and also the show, was the idea of the implications of ones actions echoing through time, DIY culture (like the Dub sound-system

scene) as a act of resistance from within an system, and fecundity.

Fecundity is basically the opposite to monopoly. I know today we are obsessed with the idea of the individual genius. It fits

with our capitalist framework of thinking. But Elon Musk or Sam

Altman aren’t going to save us. What is going to save us is societal fecundity – the ability to produce an abundance of new

ideas. The American social theorist Murray Bookchin had a theory on how a society should foster this:

“Consensus mutes dissonance […]

minorities and the right to form factions, and the right to dispute, and to

organize around issues in opposition from one point of view to another […] the

right to have this is the only way you can have a creative body politic because

it is invariably, or almost invariably, the fact that by dispute, by the

absence of consensus, by an attempt to cultivate minorities, and to let them

function freely as minorities in an organized way is the only way we can

produce a creative society. We had to be able to create, and to be able to

create we had to cultivate the minorities - that come out often with the most

advanced points of view.”[1]

Big thanks to Roots Modulation Sound-System & Erik Söderberg.

[1] M. Bookshin ‘One of

Murray Bookchin's last Interviews (2004)’, 38:00, https://youtu.be/f8fdPbLeQvE?si=X4drWa_XvBaAqfXY

I guess if you have made it this far you might also find interesting:

Babylon (1980) by Franco Rosso

Lovers Rock (2020) by Steve McQueen

No One Is Bored,

Everything Is Boring by me (Lewis Henderson)

The

Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte by Karl Marx

Roots Modulation Sound-System & Erik Söderberg

Anything by Murray Bookchin

Back<

Let us imagine that moved by jealousy, curiosity, or vice I have just glued my ear to the door and looked through a keyhole. I am alone and on the level of a non-thetic self-consciousness. This means first of all that there is no self to inhabit my consciousness, nothing therefore to which I can refer my acts in order to qualify them. They are in no way known; I am my acts and hence they carry in themselves their whole justification. I am a pure consciousness of things, and things, caught up in the circuit of my selfness, offer to me their potentialities as the proof of my non-thetic consciousness (of) my own possibilities. This means that behind that door a spectacle is presented as "to be seen," a conversation as "to be heard."

...

But all of a sudden I hear footsteps in the hall. Someone is looking at me. What does this mean? It means that I am suddenly affected in my being and that essential modifications appear in my structure - modifications which I can apprehend and fix conceptually by means of the reflective cogito.

First of all, I now exist as myself for my unreflective consciousness. It is this irruption of the self which has been most often described: I see myself because somebody sees me - as it is usually expressed.

...

Only the reflective consciousness has the self directly for an object. The unreflective consciousness does not apprehend the person directly or as its object; the person is presented to consciousness in so far as the person is an object for the Other. This means that all of a sudden I am conscious of myself as escaping myself, not in that I am the foundation of my own nothingness but in that I have my foundation outside myself. I am for myself only as I am a pure reference to the Other.

Photo of Lee “Scratch” Perry that I took back in 2013 when I interviewed him for NU Magazine

I guess if you have made it this far you might also find interesting:

More text after documentation.

More text after documentation.